100 years of MPA, 100 years of Transatlantic Cooperation (2)

Early Stirrings of MPA’s International Focus

From its earliest days, the MPA and the industry we represent aspired to deliver entertainment to audiences around the world.

The medium of film was, of course, far from just a “Hollywood thing.” The industry was from the outset, and is today, both global, human, and forward facing: the stories we write, loved by so many, thrive on cultural exchange and on daring audiences to look beyond the horizon.

On the eve of World War I, in the summer of 1914, the Famous Players company boarded an ocean liner to Rome to shoot what was perhaps the first U.S. studio film made in Europe – a silent film titled The Eternal City (now lost).

“A week ago, the only thing I thought was out of the ordinary was that it was my birthday.”

Jim Carrey as Walter Sparrow in The Number 23

By 1921, Paramount Pictures (the successor to Famous Players) launched the European Film Alliance (EFA) and acquired the most modern studios in Germany. The EFA hired many German creators who had previously worked for the German Universum AG (UFA), such as Honorary Academy Award winner Ernst Lubitsch.

Despite the EFA being short-lived, Paramount Pictures and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) stepped up in 1925 to save the UFA from bankruptcy, after the German studio had overspent on its production of Metropolis. As a result, Paramount Pictures, MGM and UFA formed the Parufamet distribution company that same year.

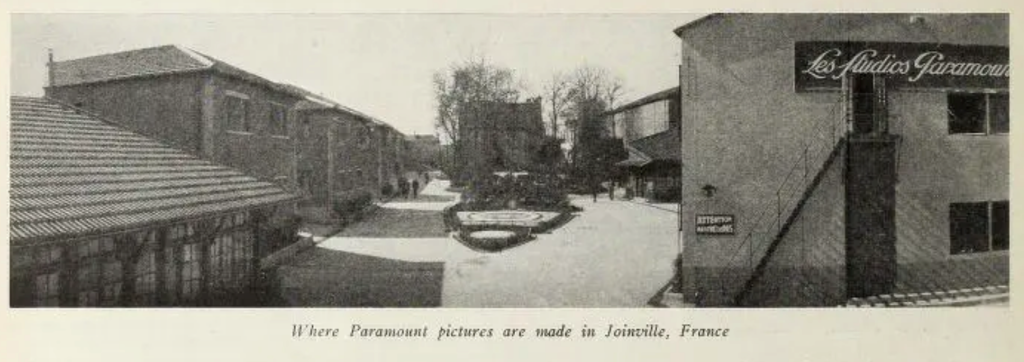

With the advent of sound in the early 1930s, Paramount established a production operation near Paris to make “talkies” in multiple language versions. A piece in Le Figaro recalls how Paramount executive Bob Kane helped to attract the brilliant French writer Marcel Pagnol to join this early effort. (For more on this interesting period, check out the blog post Paramount in Paris.)

Like Paramount and other studios, the MPPDA (aka “Hays Organization”) confirmed its commitment to international markets as early as 1924, when the association hired former U.S. diplomat Frederick Herron to lead its International Department. A year later, the association established its presence in Europe by hiring former U.S. diplomat Harold L. Smith as its first European representative, based in Paris.

Early records show that the association’s priorities in those days were not so different from today: Objectives included protecting copyright, fighting piracy, and enabling audiences around the world to see and enjoy their members’ films.

The early transatlantic relationships of the 1920s and 1930s presaged how important transatlantic cultural cooperation would become to the future of film. Even decades later, French cinema’s novelle vague (new wave) that began in the late 1950s would inspire pathbreaking Hollywood films like Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and Easy Rider (1969) among many others.

Of course, World War II would bring an abrupt end to transatlantic cultural and commercial cooperation among filmmakers. I’ll take a look at that that period in my next blog post.